Comments

'And finally, not everyone’s being doing topical. In fact, here’s the rather lovely 6 Oxgangs Avenue devoted to the history of the development of the area, this week highlighting how the block of flats came into being. Could have been prompted by Who do you think you are? Or just a timely reminder that not everything worth blogging about is in the here and now.'

Kate Higgins, Scottish Roundup 26/08/2012

Friday, 24 October 2025

The Last of the Mohicans

24th October 2020

I took the opportunity to look into T.H. Downes greengrocer’s shop in Colinton Village. I was right with my earlier musings that it is indeed Patsy’s brother who since she died back in March aged 81 years has been trying to help it to limp along. He’s 77 years old, so younger than her. Because of a rotor-cuff injury he’s unable to continue working at the nursery. He remarked how he couldn’t but wonder how Patsy had spent over 60 years in the shop. He found himself getting bored but said he enjoyed people coming in for a blether. As would she. But she was also a great reader, rarely to be found without a book in her hand. If I recall correctly, she liked James Paterson. I took several photographs.

In comparing them to others I’d taken previously he’s maintained most of the shop’s vintage feel. He’s also increased the stock and the range. I’m glad I visited. One day, probably sooner than later, I’ll drop by and find the business has closed for good, after operating for over a century.

After a century of being in the family, January 2023 marks the end of an era with Downes’s greengrocer shop in Colinton Village currently up for sale.Tempus fugit. And The Last of the Mohicans.

Wednesday, 10 September 2025

Annette - Sweet on You

Chapter 43 Annette – Sweet on You (Extract from the book Two Worlds)

Annette Motley nee Combe, with her mother Catherine

Picture courtesy Tony Combe

During Arthur’s first year at university he had met a young lady – a local girl who was aged only around sixteen at the time. Her name was Annette Turnbul Combe and she would go on to to become a significant ongoing presence in his life.

As to when he first met her we don’t exactly know, but given the nature of the relationship and what was to thereafter occur it would most likely have been at a relatively early stage in his first year at the University of Edinburgh, so perhaps during late autumn 1928.

By the start of his first academic year in October 1928 we’re fairly certain that Arthur is now residing in lodgings at 25 Marchmont Road.

It’s only an informed guess but it was perhaps whilst on his way to and from the university that he first met young Annette Combe within the general vicinity.

My mother seems to recall that her parents – or at least her mother - ran a sweet shop selling newspapers, cigarettes, confectionery, etc. Perhaps Annette worked part-time in the shop and it was here in the premises that their paths first crossed.

Editor’s Note Come the 9th September 2025, after meeting up with Annette and Arthur’s nephew, Tony Combe, it does indeed appear to be the case that Annette’s mother, Catherine Combe, now separated from her husband David, does indeed run a sweetie shop in the area. See postscript vignette, Shop-Keeper and Assistant.

I suspect Arthur may have enjoyed both a smoke and a bar of chocolate.

When you visit a shop regularly it allows you to build up an easy rapport and quick relationship with the owners and the staff.

Each day you superficially pass the time of day - how you’re getting on – and gradually as you get to know one another better you exchange what’s going on in your day to day life too.

Here in Britain – and Edinburgh is no different to cities in England – such conversations famously begin with comments about the city’s variable weather and before you know it you’re discussing school, university, work and family background.

As a business one of the key tricks is to please your customer so that they come back time after time after time so that they become one of your regulars: it’s not simply a transaction but instead you develop a relationship with your customers.

You want to be friendly but in doing so by trying to seek out the right balance – not being too nosey – too inquisitive, but being interested in your fellow traveller’s life and when appropriate being supportive too.

If Annette worked in the shop she would have been pleasant to Arthur. They were both young – Arthur was 24 and Annette aged around six or seven years younger. Indeed, she may still have been at school only helping out in the shop occasionally.

She would have found Arthur interesting, perhaps even an exotic creature – he was handsome – he was Black – he had an attractive personality and disposition – he was charming, fun, optimistic, with a ready smile and a hearty chuckle.

And he was different – very different to the other young Edinburgh men who frequented the shop and with whom she had come across, albeit, with students living within the Marchmont area and community, Arthur wouldn’t have been the first coloured man that she had met. But nevertheless she was attracted to him and found him fascinating too.

But given the prevailing ambience and culture of Edinburgh, how on earth did their relationship develop beyond simply a short pleasant exchange, encounter and chat within the confines of a shop across the counter as Arthur passed his farthings, halfpennies, pennies, sixpences or shillings across to Annette in exchange for a bar of Cadbury’s chocolate or a packet of Woodbine, Gold Flake or Players Navy Cut cigarettes?

And in developing further the notion - the concept or theory of transactions versus relationships in the world of business and clients and customers - how on earth did they first move from it being a transaction to a relationship in its more fullish – or should that be foolish – sense?

At the time – late 1928 - the barriers would appear to have been insurmountable, but as the cliche goes, love will find a way.

Beyond the shop one other likely way whereby they may have met is if they had both attended the same local church.

I don’t recall Dr Motley being of a religious persuasion but it does state in the Lincoln University CV that he was a philosopher of religion, so who knows.

With his father Frank going on to become a minister clearly his parents were religious. But outwith that unless there was perhaps a local party at around Christmas or New Year the only other possibility is that they may have passed each other in the local streets and got to know each other in brief little exchanges.

But beyond that, in Calvinist Edinburgh with its colour bars in some parts of the city, if they were to have been seen out and about as a couple together in each other’s company, it would most certainly have turned heads.

They say Edinburgh is a village – that you’re only one link away in the chain from knowing someone in common - and in a community such as Marchmont and given Annette’s parents were shop-keepers, what with the regular flow of customers coming in and out of their shop each day, if the young couple had been seen out and about together, no doubt word would have spread very quickly and got back to them.

And whilst their colour difference at the time would have been a major barrier, this was further exaggerated by Annette being so young and still a local schoolgirl.

Annette may have attended the well regarded George Watson’s Ladies College school better known as George Square named after its location in the city close-by the university: alternatively she may instead have been at the local school in Marchmont - James Gillespie School for Girls made famous by its most famous alumni Dame Muriel Spark with the school becoming legendary as where ‘Miss Jean Brodie’ taught when she was in her prime.

Writing of this does of course raise the possibility that if Arthur and Annette had got to know each other through the shop, on occasion they may also have followed a very similar route home to Marchmont, she after school and he after being at university, giving them an opportunity to meet.

So perhaps on occasion they accidentally bumped into each other enjoying each other’s company as they casually and easily chatted about their distinct and different young lives and backgrounds – she an Edinburgher and he an Okie.

And thereafter, as their relationship developed, rather than serendipity bringing them together, as the weeks and the months passed by, in the harmony of the Edinburgh seasons - autumn through the bitter winter of 1929 when Arthur kept warm in Annette’s arms and sweet embraces and then into the darling buds of May and early summer, their love for each other grew and grew until their passion spilled over in that first week or so in May when they first consummated their relationship.

But certainly when Annette had started seeing Arthur it’s something that wouldn’t have gone un-noticed and it would surely have been spotted by one of the girls from Annette’s school and no doubt word would have got out and quickly spread.

It would have been the stuff of gossip.

The Meadows on Sundays has always been a popular Edinburgh haunt for courting couples but it would have been well nigh on impossible for Annette and Arthur to have been like other lovers and instead they would have had to have conducted a more clandestine affair.

And yet, an affair there was – a love affair – so the young couple must somehow have managed to find a way because during the height of when Arthur should have been studying hard for his first set of medical examinations and sitting the written and oral papers he and Annette conceived a child.

Thursday, 1 May 2025

The Last of the Mohicans

'Am I wrong to think that we delighted in living there? No delusions are more familiar than those inspired in the elderly by nostalgia, but am I completely mistaken to think that living as well-born children in Renaissance Florence could not have held a candle to growing up within aromatic range of Tabachnik's pickle barrels? Am I mistaken to think that even back then, in the vivid present, the fullness of life stirred our emotions to an extraordinary extent? Has anywhere since so engrossed you in its ocean of details? The detail, the immensity of the detail, the force of the detail, the weight of the detail—the rich endlessness of detail surrounding you in your young life like the six feet of dirt that'll be packed on your grave when you're dead. Perhaps by definition a neighbourhood is the place to which a child spontaneously gives undivided attention; that's the unfiltered way meaning comes to children, just flowing off the surface of things. Nonetheless, fifty years later, I ask you: has the immersion ever again been so complete as it was in those streets, where every block, every backyard, every house, every floor of every house — the walls, ceilings, doors, and windows of every last friend's family apartment — came to be so absolutely individualised? Were we ever again to be such keen recording instruments of the microscopic surface of things close at hand, of the minutest gradations of social position conveyed by linoleum and oilcloth, by yahrzeit candies and cooking smells, by Ronson table lighters and venetian blinds? About one another, we knew who had what kind of lunch in the bag in his locker and who ordered what on his hot dog at Syd's; we knew one another's every physical attribute — who walked pigeon-toed and who had breasts, who smelled of hair oil and who over salivated when he spoke; we knew who among us was belligerent and who was friendly, who was smart and who was dumb; we knew whose mother had the accent and whose father had the moustache, whose mother worked and whose father was dead; somehow we even dimly grasped how every family's different set of circumstances set each family a distinctive difficult human problem…’

Philip Roth, American Pastoral

In 1958 the Hoffmann family – my father, Ken Hoffmann aged 32, Mother 22 and myself 2 years of age all moved into one of the ground floor flats at the newly built 6 Oxgangs Avenue.

My parents had married in Dalkeith in 1955.

At the time Mother was only nineteen years of age and had just finished her first year at Edinburgh University. Father was a Chief Officer in the Merchant Navy. As Mother used to say she met her doom at the Plaza Dance Hall in Morningside.

She never returned to university much to my grandmother’s great disappointment.

After they’d married they spent the first few years living at my grandparents’ home at 45 Durham Road Portobello before living for six months in a flat at Duncan Street with Mother’s cousin Margaret and Andy Ross; they too had a young child, David, who is of similar age to me.

My brother Iain was born on the 29th November 1958 whilst my sister Anne completed the family being born at

home at 6/2 Oxgangs Avenue on September 19th 1961. Around 1970 my mother went out to work in the Civil Service at the Department for Agriculture & Fisheries Chesser House and then later moved on to the Scottish Office at the New St Andrew’s House offices at the St James Centre.

We remained at 6/2 as a family unit until 1971 when my parents divorced on my 15th birthday. Later that summer Mother married John Duncan who at the time was a P.O. in the Royal Navy. The following year, 1972, come St Andrew’s Night, I left Oxgangs and the family home.

In the 1950s the Prime Minister, Mr Harold Macmillan, told the electorate that they had never had it so good.

His comments were partly based on the progress made in implementing the Beveridge Report and tackling the five evils of want; ignorance; disease; squalor; and idleness. The young families who moved into the newly built 6 Oxgangs Avenue in 1958 were direct beneficiaries of what men had gone to war for and the new vision of a country fit for them to live in afterwards.

Generally the families who lived in the Stair at number 6 lived in harmony. Yes, there was occasional friction, but it was very mild and occasional.

All the families were good neighbours.

The culture was a happy one which probably reflected the optimism of the 1960s.

Compared to the housing which had existed a decade earlier, the modern flats and new housing schemes with their indoor loos and open coal fires were great places to live and bring up young families. Children played safely.

There were formal playgrounds, sports pitches and tennis courts; and we could easily go off for youthful adventures to Redford Burn, the Army’s polo fields and Braidburn Valley all of which were on our doorsteps.

One hundred yards away was Dr Motley's surgery and Mr Russell the dentist at Oxgangs Road North.

There was a new school with the beautiful title of Hunters Tryst which was set in lovely spacious grounds with large playgrounds, a small wood and football pitches.

It was a period of stability.

Families were generally happy.

Despite the daily grind and drudgery, mums and dads enjoyed the novelty of parenthood.

Women were mainly the homemakers, men were the breadwinners.

Access to employment was relatively easy.

No one was well off and each household could be described as working class. At The Stair, no one owned a car, however people weren't desperately poor either, even if Child Benefit made the difference between eating or not The Stair reflected the changing decades.

If the 1970s were about strife, then some of the new inhabitants were not as neighbourly. The 1980s of Mrs Thatcher led to families buying their own houses. The 1990s were a period of growth, better wages and no doubt those now at number 6 will have enjoyed foreign holidays and car ownership. By the Noughties the impact of the recession could be seen and the Stair was looking a little neglected - hardly surprising given it was now fifty years since it was built.

The Swansons were our next door neighbours, living at 6/1 Oxgangs Avenue. Dougal Swanson worked as a shop assistant at James Aitkenhead’s Grocery shop and then as a stock-keeper at Brown Brothers Engineering Company.

As for our father, Ken Hoffmann (6/2), well, Mother gave up counting at thirty, the number of jobs he had been employed in - assistant cinema manager; stock clerk; lorry driver for George Bain’s delivering meat to butchers’ shops in Edinburgh and the Borders and also as a long distance driver for John Bryce Transport.

However he had also been a Chief Officer in the merchant navy, training at the renowned Edinburgh company, Ben Line. His qualification was probably the equivalent of a degree in physics or maths, however those were before the days of NVQs so he found he could not use transferable management skills to gain better employment. The other issue was that being an alcoholic made it difficult for him to hold down a job for any length of time.

Mr Stewart (6/3) was a policeman and like many others in that line of work kept himself to himself, a complete distance from any other neighbour in the Stair. Even today, I think policemen and women are expected to maintain a certain distance as are teachers from participating on social media.

George Hogg (6/4) was a joiner. George was part of a small cooperative of skilled tradesmen who in later years built their own houses toward Oxgangs Green.

Charles Blades (6/6) worked for many years at Ferranti's where he was a personal assistant to Basil de Ferranti.

He regularly accompanied him to meetings in London. Whilst in the Army Charles had initially trained as a doctor but late on in the course dropped out. Like my father, he too was an alcoholic. This prevented him reaching his full potential. This condition blighted the lives of both families. Dougal, Ken and Charles were clearly bright individuals and incredibly

Charles’ father was Lord Blades, the respected judge and appointed the Solicitor General for Scotland at the end of the war in 1945.

Charlie Hanlon (6/7) worked for many years at the Uniroyal Rubber Mill which superseded the North British Company - a steady and secure job for many years. He worked shifts. Sometimes Hilda would hang out the top floor sitting room window and chastise the kids down below for being too loud and ‘keeping my Charlie awake when he's on the night shift!’ I liked the way Charlie brought home a Friday treat of chocolate bars for his four sons, Michael; Boo-Boo; Colin; and Alan. If you'll forgive the pun, it was a sweet thing to do.

Meanwhile, Mr Duffy (6/8) was a general labourer and scaffy in later years; previously he may have worked elsewhere but that change may have been brought about because I think he lost his driving license.

In the original Oxgangs book, The Stair, Mother is of course one of the (many) stars of the Stair, featuring prominently in it and the two books which superseded it, Oxgangs A Capital Tale Volumes 1 and 2.

There are many stories there in which she features. But, it’s in the different seasons and seasonal festivities in the calendar year, that I recall her best.

Easter was always an important staging post in the year. It was then that we received our personal mugs (decorated with a cartoon character holding a chocolate egg) to last us the rest of year for our cups of tea – yes, in the 1960s we children drank tea from a relatively young age.

During the 1960s there were regular wee family picnics in the summer to Braidburn Valley.

When the sun came out then Helen Blades (6/6) came out! There's a nice correlation there - Helen loved the sun and grabbed any opportunity to sun bathe and to get a little colour. The front of 6 Oxgangs Avenue was north facing and busier with road vehicles and passersby, whilst our back garden was quieter and a lovely sun trap. It was here that Helen, Marion Dibley (4/4) and Mother would often sit out in the garden on chairs or blankets with their backs to the shed wall and the sun on their faces, whilst they enjoyed a cigarette and a blether. As Mother says, who could ever forget Helen's marvellous deep throaty laugh. She and Helen were quite friendly, but with young families usually always too busy to spend much time together. We children often sat around to listen in to Helen, Marion and Mother.

When our father played cricket for Boroughmuir down at Meggetland, the cultural tradition was for all members of each team and the officials to bring along a contribution to the spread for afternoon tea. It was a Hoffmann team effort in this endeavour. I had to nip down to The Store (St Cuthbert’s Cooperative) at Oxgangs Road North to buy in a couple of large jars of Shippam’s Paste and unusually for us a Sliced Pan loaf - easier than our staple the Sliced Plain to make sandwiches with. Mother would then make up the sandwiches spreading them with Stork margarine and applying the paste; the sandwiches were then wrapped up in the bread-wrapper. Father had the glory leg - his role was to carry the sandwiches down in the 27 bus along with his cricket grip (bag) and put them on the long trestle tables inside the pavilion concourse.

No one will likely recall Shandon Records which back in the mid-1960s was located around Stewart Terrace. Many decades ago it headed off to the great record shop graveyard in the sky. It wasn't large - just a small dinky little hole in the wall shop, selling second hand records but it carried an interesting stock and represented great value for your money. After we got our first little suitcase record player, one summer Mother and I took a few trips on the number 4 bus from Oxgangs down to Shandon to see what little gems we might pick up. I enjoyed those little summer interludes together, finding it a rare interlude for just the two of us to bond together.

Apart from Mother holding the purse strings she also had a surprisingly deeper knowledge of music than me. So, initially whilst I might not be overly-happy with her choice of record from our limited budget, once back home to 6/2 Oxgangs Avenue I would realise we'd struck gold.

On one such occasion she picked up Guantanamera by The Sandpipers; I had my doubts but it was a beautiful track as was Nancy Sinatra and Lee Hazelwood's 'These Boots Were Made For Walking'with the B side the hauntingly dreamy Summer Wine.

And when we grew a little older and after our parents were divorced, Mother, at last, used her Edinburgh University education and got a job in the Civil Service at Chesser House in Agriculture and Fisheries. As with Springsteen’s feelings about how proud he was of his mother going off to work, smartly and immaculately dressed, I too felt just the same. Anne, Iain and I shared some of the burden. We tidied the house; made the fire; did the messages; and washed, dried and put away the dishes. We took a certain pride in having the place looking ship shape for Mother arriving home at tea time.

Those were happier days for us at 6/2. Home was a much more relaxed place to be. It was an inviting happy place to hang about and our pals enjoyed it too. Come the weekend, we’d often see Paul Forbes; Ali Douglas; Les Ramage; Boo Boo and others enjoy a sleepover with us sitting up late into the night with our bags of crisps and chips, sweets, chocolate and Globe Red Cola to watch the Friday evening horror film. Very much, changed days from when our father was there previously.

With Mother earning a good income, we received some greatly valued items, mainly as birthday or Christmas presents,but sometimes outwith too but usually only after pestering her to death. Iain got a rather wonderful Johnny Seven Gun as a birthday present and also the James Bond Aston Martin car with the ejector seat which featured in the film Goldfinger.

He also got a nice slot car racing game - it wasn't Scalectrix but it was good quality and great fun to play with. Iain and I also each received a pair of the famous Wayfinder shoes. They had a secret compass hidden inside one heel of a shoe and had animal tracks impregnated on the soles. I wasn't sure how many of these animals roamed around Oxgangs not to mention it being a pain to keep taking your shoe off if you wanted to track down a wild beast; and then what were we supposed to do if we came across such a wild creature in the locality – perhaps carry Iain’s Johnny Seven gun!

When I began to go along to the Edinburgh Athletic Club in 1971 Mother pushed the boat out and bought me a good tracksuit and a particularly stylish pair of training shoes. They were similar to Adidas with three stripes, two of which were blue and one red. When that parcel arrived on the doorstep it was a happy day and a life changing event for me. Indeed, whenever we awaited an order the first thing we asked when we got home from school was 'Has it arrived yet?' Disappointment followed disappointment and then exhilaration on the magical day when we came home to discover a large, bulky, brown parcel.

Mother was a great reader, enormously well-read. Indeed in her later years, when suffering some of the vicissitudes of old age and poor health, she was at least temporarily, able to escape for a wee while to a hidden planet (Denis Healey) for some respite.

Back in the 1960s we got our books from the Edinburgh Corporation Mobile Library. The library was parked on the corner of Oxgangs Terrace on Tuesdays and Fridays. We read more in the second half of the year. On late autumn afternoons or dark winter evenings it was always a lovely break to venture down with Mother to the mobile library and step inside and be transported to another world. The children's books were kept at the rear of the van up the little steps. My favourites were always the Folk Tales or Fairy Tales of other lands in particular Rumpelstilskin or The Tinder Box.

Today Oxgangs has an excellent library. When it first opened I recall Mother and me attending some of the wonderful events that they promoted including daring to mischievously ask the beautiful Edna O'Brien about a passage to do with her relationship with John Huston from his book An Open Book which threw her somewhat - how the heck was someone from little old Oxgangs aware of that! David Daiches was at another of their special evenings and we were able to get him my to sign my treasured copy of the finest and most evocative book ever written about the capital, Two Worlds.

Serendipity or what but twenty five years later the world moves full circle and in 2015 I was privileged and delighted to be invited back to Oxgangs Library as one of their authors as part of their anniversary celebrations of the opening of the library.

But it’s mostly at Christmas time that I recall Mother best of all, when she always ensured that no matter how poor we might be, Father being an alcoholic, perhaps unemployed, how she always ensured Anne, Iain and I always received an exciting, colourful, thoughtfully put-together stocking containing all sorts of lovely serendipities.

And what of 6/5 Oxgangs Avenue? Well, I’ve kept Eric Smith (6/5) aged 91, for last, because Eric’s now the last living adult member from the original Stair, as I recall it. Eric worked as a general helper at Marks and Spencer. This was a secure job; previously he may have been a bus driver, but his wife, Mary, didn’t like him working shifts. Today Eric lives happily in a care home in Colinton.

With the death of my mother Mrs Anne Duncan (formerly Anne Hoffmann) aged 89, last Tuesday evening, Eric is now the last of the Mohicans.

Peter Hoffmann

Thursday, 17 April 2025

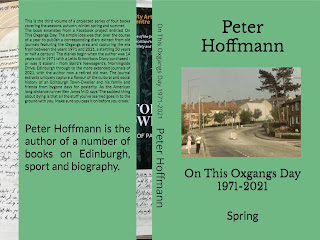

On This Oxgangs Day

The blog for today, (16th April), is taken from the Facebook group 'In The Season of the Year - An Oxgangs Diary' published each day. Two books capture these extracts are displayed in the photo attachments, one covering Spring (February - May) 'On This Oxgangs Day 1971-2021 Spring' with multiple entries for each day from across half a century. The other book 'In the Season of the Year An Oxgangs Diary 1971-2021' covers a single Oxgangs related post for each day of the year. Both books are available through Amazon.

16th April

1983 (Age 26)

We took a 42 bus up to Causewayside where I picked up a delightful wee book on the Pentlands – Pentland Days and Country Ways by Will Grant, for only £2. It’s a while since I’ve been up there. It’s also good that we’ve a couple of local second-hand bookshops close-by the flat at Canonmills.

In the evening I completed Magnus Merriman – at last. I guess overall it’s been okay but if it hadn’t been set in Edinburgh I would have thought ill of it. I feel it’s over-rated, definitely a one–off read.

Later on I laughed and laughed at Clive James’ Late Late Show. 😂

Earlier around 9 o’clock I poked my head out the back door at the drizzle coming down. To my surprise I noticed the pear blossom seems to be out.

1984 (Age 27)

After such a long day, I ought to have dark rings under my eyes.

It was the Edinburgh Spring Holiday and a sunny one too, but with a cold wind. Martha was working. I was off.

After a gentle early morning jog and a light breakfast I drove across a quiet capital picking up a Scotsman newspaper at Lennox Newsagent’s, Comiston Road, en-route to Swanston Village.

From there I walked up Allermuir, stopping every now and then to look back toward the north and across the city taking in the views. A tractor-man was already out, the life on a spring morning. There were also two shepherds out, checking on lambs. I was quite amazed at the speed with which they walked, one of whom looked about 60 years old. Such an outdoor life obviously keeps you fit. Similarly when I drove past Swanston Farm, I’d noticed a very fit looking older farm-worker. As I gradually walked up toward the summit I was surprised at just how hard I was breathing and also how wobbly my legs were.

On the summit itself, in the shady parts, there was still a heavy frost. There was a snell wind a-blowing. However, I managed to find a sunny sheltered spot, stopped off for black coffee and some bran biscuits. In between looking through my small binoculars taking in the panoramic views across Edinburgh, to Fife beyond, I read some extracts from Stevenson’s Letters (Vol 1).

Mid-morning I headed down to Oxgangs to pick up Mum. We drove down to Porty to pick up Grandma Joan and Aunt Dottle before setting off for Peebles via the bonny Meldons. We enjoyed a filling lunch at Innerleithen and of course a Caldwell’s ice cream. The shops at Peebles were busy. On an Edinburgh Holiday it’s clearly a popular haunt. We took an alternative route home, via Stobo, Broughton, before stopping at an antiques shop in West Linton. Joan very much enjoyed herself, but I was less sure about Dottle and Mum.

After dropping them off I did a wee track session on the Edinburgh University track out at Peffermill. And then home, appropriately enough to watch the first part of Stevenson’s The Master of Balantrae. I found it poor, unrealistic, with stilted dialogue. I was reflecting upon how very unfortunate that RLS died so young, as the unfinished Weir of Hermiston hinted at some very special work ahead. A great pity.

Anyway I was glad to have taken Grandma Joan out today. She may not see many more Spring Holidays (famous last words!) Today, her eye was giving her problems, with a thread running through her vision. I hope it’s nothing serious.

Labels:

Allermuir,

Caldwell Ice Cream,

Innerleithen,

Lennox Newsagent,

Pentland Hills,

Robert Louis Stevenson,

Stobo,

Swanston Farm,

West Linton,

Will Grant

Sunday, 13 November 2022

Saturday, 12 November 2022

Friday, 11 November 2022

Dr Motley - The War Years Chapter 101

After qualifying in 1939 and passing his L.M.S.S.A. exams in London shortly before developing his own practice in Oxgangs, an external force was about to impact upon Arthur and millions of people throughout the world – Britain had declared war on Germany.

They say it’s an ill-wind that blows no good, but for Arthur there was one positive outcome from Neville Chamberlain’s announcement on the 3rd September 1939 that Britain was at war with Germany.

The War was about to affect the trajectory of the now Dr rather than Mr Arthur Philip Motley’s life.

With him being so very recently qualified and inexperienced the War provided him with the opportunity to practice - to ‘experiment’ – to learn on the job so to speak - on young Forces’ personnel over the course of four or five years and all at a very fast pace.

Whilst it may sound crude, having young and fit men to administer to would have been a useful learning ground and he would have had back-up too in terms of access to medical staff with far more experience than him – after all he had only recently qualified in the year that the War began – 1939 – and by the following year, 1940, he was part of the Royal Army Medical Corps - the R.A.M.C.

One aspect of his new expertise as recorded in The Medical Directory was that he was experienced in venereology!

In his capacity as a medical officer he could now learn on the job and develop his skills and knowledge as well as his bedside manner, especially as his patients would be mainly white. And it was from that experience that gave him the confidence that whilst in some parts of Edinburgh a colour bar remained, he would realise that it wasn’t a complete barrier to achieve his dream to become an Edinburgh doctor.

We have very little information of the newly qualified Dr Motley’s time in the R.A.M.C. over the next five years or so other than he was appointed as a Lieutenant on the 27th September 1941 and whilst serving would have been made a Captain (Regular Army Emergency Commission). He was awarded the War Medal 1939-1945 and also the 1939-45 Star for operational service.

The War Medal was awarded to all full time service personnel who had completed at least 28 days of service. The Star was awarded for operational service.

What is interesting is that his record is on a U.S. World War II draft card, not a British one: he remained an American citizen and not British. However, what we can garner from the card are two further points.

First of all, his point of contact is not his wife Annette in Edinburgh, but instead, his mother, Ethel – Mrs R.F. Motley back at 902 East Monroe Avenue McAlester City Oklahoma.

Once again this is suggestive that neither his mother nor his father were aware that Arthur, aged 33 – at least according to the record card – actually 36 - was married.

But in terms of his war service it denotes that his address is 13 General Hospital British Middle East Forces, so he is in all likelihood now abroad. That it doesn’t state a specific location is

for reasons of security.

Therefore not long after qualifying as a doctor, but with some limited first aid practical experience garnered from working in earlier years as the Honorary Medical Officer at the Colinton Mains First Aid Post, Dr Motley was conscripted into the Army.

Aged 36 – not young for joining the army - and no doubt he would have lost a lot of general fitness since he last played American Football back at Lincoln University Pennsylvania over 13 years previously, so alongside all the other dramatic changes, the new lifestyle would have come as a bit of a cultural shock to him.

Unlike many soldiers he was not only twice the age of many of the new recruits, but he was married, he was a father, he was American and he was Black.

That would have made him stand out.

But as is the way of Forces’ humour it would have stood him in good stead for the future after the War not only preparing himself for a future medical career but in dealing with the joshing and joking that would have gone on – army humour – his mates wouldn’t have been averse to giving him an un-PC nickname – but he would also have learnt that behind this, there was no often no real ill-will or malice toward him – instead he was one of the boys and it would have further developed his skills to ride the punches and win others over with his sense of good humour as well as his kindness and gentleness too.

In 1941 he would have taken the long train journey from Edinburgh down to Aldershot to begin his medical training. Even today that journey takes around ten hours but back in 1941 it would have taken a great deal longer as the great steam engine puffed its way southwards from Scotland’s capital.

Did Annette Motley and their daughter now aged 11 and about to start secondary school the following year see him off at Waverley Station or did they instead say their goodbyes earlier that autumn morning back at Colinton Mains Road just as Annette Junior set out for school.

It would have been a very worrying time for the three of them.

It would have been very scary for Dr Motley, but also for the two Annettes not knowing whether they would ever see their husband and father again – theoretically, that September morning of 1941 could have been their last time spent together.

But instead we of course know that Dr Motley fortunately survived that terrible period in world history, but those were pivotal years for Annette Junior – when her father left Edinburgh she was but 11 years old; when his tenure in the Army ended she was aged around 16 - a key period in her life and one where most of the parenting duties fell upon her mother Annette.

In its own way this must have impacted upon each of the different relationships within the family and does beg questions as to some of the information which Yvonne Herjholm provided decades later relating that the Annettes had a poor relationship with each other.

But come the autumn of 1941 when Dr Motley set off on that long train journey it was moving toward the end of what had been an incredibly tough year for Britain testing her resilience to the full, particularly in the southern capital of London.

The Blitz – German for lightning – only ended in the spring and the May of that year: a million houses in the capital had been damaged – a very heavy toll. Over that earlier eight month period over 40,000 civilians had been killed.

Fortunately, on British soil there was now a slight reprieve as Hitler’s attention transferred to the Eastern Front and Operation Barbarossa. But when Dr Motley set off on that fresh autumn morning he would have had no idea as to where he might be posted.

When Dr Motley joined the R.A.M.C. because it’s the autumn of 1941 we’re aware America had not yet entered the Second World War not doing so until the 8th December 1941 when it declared war on Japan and then three days later on the 11th December 1941 it declared war on Germany. And therefore strictly speaking, as an American citizen, Dr Motley could have left his Forces’ tenure for a further few months not joining up until the end of the year or indeed into the following year, 1942.

On his arrival at the Royal Army Medical Corps Boyce Barracks, near Aldershot, Dr Motley joined the other new recruits for training, discipline, marching, PE and lectures. Clothing, kit and equipment were issued and he would have been given a service number.

On the completion of training the new recruits were offered the privilege of a weekend pass to travel home after duty – from Friday evening through until Sunday night, but given how long that journey back and forth to Scotland would have taken and the difficulty of coordinating such a train journey I think it’s unlikely that Dr Motley would have been able to take advantage of this, tempting as it would have been.

Whilst he would have been missing his wife and daughter, he will now also have gotten into a new pattern and to disturb that for but a few hours together would have been a tough call to make and disruptive too. And certainly for some soldiers who when they did report back to barracks some were told not to bother unpacking and instead were informed they were about to embark to begin their commissions.

Based on Dr Motley’s U.S. World War II Service card we can assume that he was thereafter sent off to join the team at 13 General Hospital British Middle East Forces.

There were over one hundred such hospitals and number 13 was initially established at Tidworth Park and Leeds Malmesbury, however by the time Dr Motley joined the unit they had moved out six months earlier to the British Military Hospital in Suez.

Whilst Dr Motley would have initially had no idea where he was being sent to it’s most likely he would have sailed in a converted troop ship with thousands of other soldiers on board alongside dozens of doctors from the R.A.M.C. as well as dozens of nurses too. As their destination was Suez it would be via the Cape of Good Hope and then on to Egypt.

Small tugs would have assisted the boat out of dock and as the ship set sail away from England’s shores, bands may well have seen them off as well as cheers from the remaining docked ships.

Sailing beyond the River Mersey of The Beatles and Gerry and the Pacemaker pop groups fame, England and Britain would slowly and gradually fade into the distance.

The troop ship was supported from the enemy by accompanying destroyers and a fighter escort flew overhead too.

Qualifying as he did as a doctor in London in 1939 not only would alter the course of the rest of Arthur Philip Motley’s life but it may also have helped save his life too.

If he hadn’t passed the L.M.S.S.A. exams he otherwise might have found himself being conscripted and having to go off to fight the Germans rather than undertaking medical duties.

The sea journey itself would have taken around two months so alongside the previous training at Aldershot he would have got to know many more of his colleagues on board and made new friendships.

I’m unsure whether Dr Motley was a good passenger or not, but certainly I know that in later years as his newly founded Oxgangs practice developed and thrived he began to take regular cruises with his wife and I believe they enjoyed these trips very much. Indeed it was from one such trip that he became friendly with the world renowned thriller writer Ngaio Marsh who asked his permission to include him in one of her novels – a thriller which featured a ship’s doctor!

On such a long journey there would have been occasions when there was more than just a gentle sea-spray especially when the ship sailed through the North Atlantic Ocean.

Being the Forces they would have got into a new daily routine which apart from enjoying three square meals a day would have involved some drill work but outwith that there would have been plenty of time to try to keep fit and much leisure time to perhaps draft a letter home to loved ones, spend some time reading or studying or just lounging on deck enjoying the sunshine.

The food was good – better than back home, but water was scarce – a bit ironic with millions of gallons of the stuff just below the ship, so there were no baths: as to whether they could rig up some home-made showers who knows, but they arrived in Egypt rather smelly.

During the night so as not to attract enemy vessels or German aircraft there would have been a blackout in operation.

Growing up in a country where there was still segregation in place Dr Motley would have come across a different type of segregation on board ship, with officers enjoying better conditions than the common soldier.

The ship kept up a steady pace at between 16 and 21 knots.

For most of the time he would have had to wear his life-jacket probably a Kapok which some soldiers used as a pillow.

Being on board a ship that makes steady progress over the sea would have given Dr Motley much time for reflection although based on my experience of him, I’m unsure whether that was a significant part of his nature – I don’t think he was the philosophic or reflective type.

But he would have worried not just about his own safety but also about the safety of his wife and daughter back home in Edinburgh.

Although Edinburgh wasn’t at the heart of German bombing the way for example Clydebank, Glasgow or Coventry or Liverpool was, nevertheless it had been subject to irregular bombing from the start of the War in 1939.

Indeed whilst he was stationed in Suez, as late as 1943 and only a few miles south of the Motley family home at Colinton Mains Road – both Annette’s may have heard the sound of the engines of an aircraft overhead on that foggy Oxgangs evening of 24 March 1943, of a four-man German crew including Oberstleutnant Fritz Förster had earlier embarked on a mission to bomb Leith Docks aimed at disrupting wartime naval traffic in and out of the busy port.

Their Junker JU 88 had earlier left an airstrip near Paris and travelled up the Dutch North Sea coast before turning north-west towards the Firth of Forth. On their approach the crew failed to locate its target and decided to jettison their incendiary payload across farmland outside Edinburgh. But as they made their way south across the Pentlands, their plane struggled to clear the summit of Hare Hill and crashed into the hillside. Mr Förster and the other three crew were killed and the wreckage was scattered over a half-mile radius.

When Lieutenant Motley was on deck during hot days under a glowing warm sun or in the evenings when he might glance up to the heavens and to the stars and to the moon, there must have been times when he thought of his wife and daughter back in Edinburgh, Scotland and whether he might ever see them again; and if he did what would he do when he returned to secure a future for them all.

He must surely have thought too about his mother and father, Ethel and Frank, half way across the globe in Oklahoma. He recalled his boyhood and his youth and just how far he had sailed in life, but now he didn’t know whether his future journey would be either long or short.

As the troop ship made its steady progress south, by the time the boat reached the north-west coast of Africa the men were issued with Forces’ tropical kit.

Imagining Dr Motley in such attire brings a smile to my face. As I remarked and recalled in my introductory essay I say what a snappy dresser he was what with his fine suits, shirts and ties, but I don’t think tropical kit would have flattered him!

Suez would not have been the first and only port of call and en-route the ship will have docked in other ports and countries.

Sundays may have been the most delineated day of the week when a chaplain took a service on board: whether Dr Motley attended those services I’m unsure but given the precariousness of life at that time if I were to hazard a guess, I’d say yes.

The journey to Suez was via the Cape of Good Hope.

I’ve rationalised this for two reasons - firstly because the Germans and the Italians commanded the Mediterranean and secondly because of the story he told my mother of how he couldn’t go ashore in South Africa for fear of being lynched: for a while I’d slightly doubted the validity of this story but I now believe the opposite and that this would have been the only occasion he was ever in the vicinity and the port of Cape Town.

It also answers two earlier puzzles. When I’d kicked off his story I had wondered whether he had been employed or commissioned as a ship’s doctor and thus in the Royal Navy which of course cast further doubt, but I now realise the occasion of his tale arose from when the troop ship was transporting members of His Majesty’s Services en-route to Suez. Some of the troops of course would have embarked for duty in this part of the continent.

After leaving Cape Town and circling the Cape of Good Hope the ship headed north passing the opening to the Red Sea and then onward to enter the Gulf of Suez.

Thursday, 10 November 2022

Wednesday, 9 November 2022

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)