Comments

'And finally, not everyone’s being doing topical. In fact, here’s the rather lovely 6 Oxgangs Avenue devoted to the history of the development of the area, this week highlighting how the block of flats came into being. Could have been prompted by Who do you think you are? Or just a timely reminder that not everything worth blogging about is in the here and now.'

Kate Higgins, Scottish Roundup 26/08/2012

Sunday 13 November 2022

Saturday 12 November 2022

Friday 11 November 2022

Dr Motley - The War Years Chapter 101

After qualifying in 1939 and passing his L.M.S.S.A. exams in London shortly before developing his own practice in Oxgangs, an external force was about to impact upon Arthur and millions of people throughout the world – Britain had declared war on Germany.

They say it’s an ill-wind that blows no good, but for Arthur there was one positive outcome from Neville Chamberlain’s announcement on the 3rd September 1939 that Britain was at war with Germany.

The War was about to affect the trajectory of the now Dr rather than Mr Arthur Philip Motley’s life.

With him being so very recently qualified and inexperienced the War provided him with the opportunity to practice - to ‘experiment’ – to learn on the job so to speak - on young Forces’ personnel over the course of four or five years and all at a very fast pace.

Whilst it may sound crude, having young and fit men to administer to would have been a useful learning ground and he would have had back-up too in terms of access to medical staff with far more experience than him – after all he had only recently qualified in the year that the War began – 1939 – and by the following year, 1940, he was part of the Royal Army Medical Corps - the R.A.M.C.

One aspect of his new expertise as recorded in The Medical Directory was that he was experienced in venereology!

In his capacity as a medical officer he could now learn on the job and develop his skills and knowledge as well as his bedside manner, especially as his patients would be mainly white. And it was from that experience that gave him the confidence that whilst in some parts of Edinburgh a colour bar remained, he would realise that it wasn’t a complete barrier to achieve his dream to become an Edinburgh doctor.

We have very little information of the newly qualified Dr Motley’s time in the R.A.M.C. over the next five years or so other than he was appointed as a Lieutenant on the 27th September 1941 and whilst serving would have been made a Captain (Regular Army Emergency Commission). He was awarded the War Medal 1939-1945 and also the 1939-45 Star for operational service.

The War Medal was awarded to all full time service personnel who had completed at least 28 days of service. The Star was awarded for operational service.

What is interesting is that his record is on a U.S. World War II draft card, not a British one: he remained an American citizen and not British. However, what we can garner from the card are two further points.

First of all, his point of contact is not his wife Annette in Edinburgh, but instead, his mother, Ethel – Mrs R.F. Motley back at 902 East Monroe Avenue McAlester City Oklahoma.

Once again this is suggestive that neither his mother nor his father were aware that Arthur, aged 33 – at least according to the record card – actually 36 - was married.

But in terms of his war service it denotes that his address is 13 General Hospital British Middle East Forces, so he is in all likelihood now abroad. That it doesn’t state a specific location is

for reasons of security.

Therefore not long after qualifying as a doctor, but with some limited first aid practical experience garnered from working in earlier years as the Honorary Medical Officer at the Colinton Mains First Aid Post, Dr Motley was conscripted into the Army.

Aged 36 – not young for joining the army - and no doubt he would have lost a lot of general fitness since he last played American Football back at Lincoln University Pennsylvania over 13 years previously, so alongside all the other dramatic changes, the new lifestyle would have come as a bit of a cultural shock to him.

Unlike many soldiers he was not only twice the age of many of the new recruits, but he was married, he was a father, he was American and he was Black.

That would have made him stand out.

But as is the way of Forces’ humour it would have stood him in good stead for the future after the War not only preparing himself for a future medical career but in dealing with the joshing and joking that would have gone on – army humour – his mates wouldn’t have been averse to giving him an un-PC nickname – but he would also have learnt that behind this, there was no often no real ill-will or malice toward him – instead he was one of the boys and it would have further developed his skills to ride the punches and win others over with his sense of good humour as well as his kindness and gentleness too.

In 1941 he would have taken the long train journey from Edinburgh down to Aldershot to begin his medical training. Even today that journey takes around ten hours but back in 1941 it would have taken a great deal longer as the great steam engine puffed its way southwards from Scotland’s capital.

Did Annette Motley and their daughter now aged 11 and about to start secondary school the following year see him off at Waverley Station or did they instead say their goodbyes earlier that autumn morning back at Colinton Mains Road just as Annette Junior set out for school.

It would have been a very worrying time for the three of them.

It would have been very scary for Dr Motley, but also for the two Annettes not knowing whether they would ever see their husband and father again – theoretically, that September morning of 1941 could have been their last time spent together.

But instead we of course know that Dr Motley fortunately survived that terrible period in world history, but those were pivotal years for Annette Junior – when her father left Edinburgh she was but 11 years old; when his tenure in the Army ended she was aged around 16 - a key period in her life and one where most of the parenting duties fell upon her mother Annette.

In its own way this must have impacted upon each of the different relationships within the family and does beg questions as to some of the information which Yvonne Herjholm provided decades later relating that the Annettes had a poor relationship with each other.

But come the autumn of 1941 when Dr Motley set off on that long train journey it was moving toward the end of what had been an incredibly tough year for Britain testing her resilience to the full, particularly in the southern capital of London.

The Blitz – German for lightning – only ended in the spring and the May of that year: a million houses in the capital had been damaged – a very heavy toll. Over that earlier eight month period over 40,000 civilians had been killed.

Fortunately, on British soil there was now a slight reprieve as Hitler’s attention transferred to the Eastern Front and Operation Barbarossa. But when Dr Motley set off on that fresh autumn morning he would have had no idea as to where he might be posted.

When Dr Motley joined the R.A.M.C. because it’s the autumn of 1941 we’re aware America had not yet entered the Second World War not doing so until the 8th December 1941 when it declared war on Japan and then three days later on the 11th December 1941 it declared war on Germany. And therefore strictly speaking, as an American citizen, Dr Motley could have left his Forces’ tenure for a further few months not joining up until the end of the year or indeed into the following year, 1942.

On his arrival at the Royal Army Medical Corps Boyce Barracks, near Aldershot, Dr Motley joined the other new recruits for training, discipline, marching, PE and lectures. Clothing, kit and equipment were issued and he would have been given a service number.

On the completion of training the new recruits were offered the privilege of a weekend pass to travel home after duty – from Friday evening through until Sunday night, but given how long that journey back and forth to Scotland would have taken and the difficulty of coordinating such a train journey I think it’s unlikely that Dr Motley would have been able to take advantage of this, tempting as it would have been.

Whilst he would have been missing his wife and daughter, he will now also have gotten into a new pattern and to disturb that for but a few hours together would have been a tough call to make and disruptive too. And certainly for some soldiers who when they did report back to barracks some were told not to bother unpacking and instead were informed they were about to embark to begin their commissions.

Based on Dr Motley’s U.S. World War II Service card we can assume that he was thereafter sent off to join the team at 13 General Hospital British Middle East Forces.

There were over one hundred such hospitals and number 13 was initially established at Tidworth Park and Leeds Malmesbury, however by the time Dr Motley joined the unit they had moved out six months earlier to the British Military Hospital in Suez.

Whilst Dr Motley would have initially had no idea where he was being sent to it’s most likely he would have sailed in a converted troop ship with thousands of other soldiers on board alongside dozens of doctors from the R.A.M.C. as well as dozens of nurses too. As their destination was Suez it would be via the Cape of Good Hope and then on to Egypt.

Small tugs would have assisted the boat out of dock and as the ship set sail away from England’s shores, bands may well have seen them off as well as cheers from the remaining docked ships.

Sailing beyond the River Mersey of The Beatles and Gerry and the Pacemaker pop groups fame, England and Britain would slowly and gradually fade into the distance.

The troop ship was supported from the enemy by accompanying destroyers and a fighter escort flew overhead too.

Qualifying as he did as a doctor in London in 1939 not only would alter the course of the rest of Arthur Philip Motley’s life but it may also have helped save his life too.

If he hadn’t passed the L.M.S.S.A. exams he otherwise might have found himself being conscripted and having to go off to fight the Germans rather than undertaking medical duties.

The sea journey itself would have taken around two months so alongside the previous training at Aldershot he would have got to know many more of his colleagues on board and made new friendships.

I’m unsure whether Dr Motley was a good passenger or not, but certainly I know that in later years as his newly founded Oxgangs practice developed and thrived he began to take regular cruises with his wife and I believe they enjoyed these trips very much. Indeed it was from one such trip that he became friendly with the world renowned thriller writer Ngaio Marsh who asked his permission to include him in one of her novels – a thriller which featured a ship’s doctor!

On such a long journey there would have been occasions when there was more than just a gentle sea-spray especially when the ship sailed through the North Atlantic Ocean.

Being the Forces they would have got into a new daily routine which apart from enjoying three square meals a day would have involved some drill work but outwith that there would have been plenty of time to try to keep fit and much leisure time to perhaps draft a letter home to loved ones, spend some time reading or studying or just lounging on deck enjoying the sunshine.

The food was good – better than back home, but water was scarce – a bit ironic with millions of gallons of the stuff just below the ship, so there were no baths: as to whether they could rig up some home-made showers who knows, but they arrived in Egypt rather smelly.

During the night so as not to attract enemy vessels or German aircraft there would have been a blackout in operation.

Growing up in a country where there was still segregation in place Dr Motley would have come across a different type of segregation on board ship, with officers enjoying better conditions than the common soldier.

The ship kept up a steady pace at between 16 and 21 knots.

For most of the time he would have had to wear his life-jacket probably a Kapok which some soldiers used as a pillow.

Being on board a ship that makes steady progress over the sea would have given Dr Motley much time for reflection although based on my experience of him, I’m unsure whether that was a significant part of his nature – I don’t think he was the philosophic or reflective type.

But he would have worried not just about his own safety but also about the safety of his wife and daughter back home in Edinburgh.

Although Edinburgh wasn’t at the heart of German bombing the way for example Clydebank, Glasgow or Coventry or Liverpool was, nevertheless it had been subject to irregular bombing from the start of the War in 1939.

Indeed whilst he was stationed in Suez, as late as 1943 and only a few miles south of the Motley family home at Colinton Mains Road – both Annette’s may have heard the sound of the engines of an aircraft overhead on that foggy Oxgangs evening of 24 March 1943, of a four-man German crew including Oberstleutnant Fritz Förster had earlier embarked on a mission to bomb Leith Docks aimed at disrupting wartime naval traffic in and out of the busy port.

Their Junker JU 88 had earlier left an airstrip near Paris and travelled up the Dutch North Sea coast before turning north-west towards the Firth of Forth. On their approach the crew failed to locate its target and decided to jettison their incendiary payload across farmland outside Edinburgh. But as they made their way south across the Pentlands, their plane struggled to clear the summit of Hare Hill and crashed into the hillside. Mr Förster and the other three crew were killed and the wreckage was scattered over a half-mile radius.

When Lieutenant Motley was on deck during hot days under a glowing warm sun or in the evenings when he might glance up to the heavens and to the stars and to the moon, there must have been times when he thought of his wife and daughter back in Edinburgh, Scotland and whether he might ever see them again; and if he did what would he do when he returned to secure a future for them all.

He must surely have thought too about his mother and father, Ethel and Frank, half way across the globe in Oklahoma. He recalled his boyhood and his youth and just how far he had sailed in life, but now he didn’t know whether his future journey would be either long or short.

As the troop ship made its steady progress south, by the time the boat reached the north-west coast of Africa the men were issued with Forces’ tropical kit.

Imagining Dr Motley in such attire brings a smile to my face. As I remarked and recalled in my introductory essay I say what a snappy dresser he was what with his fine suits, shirts and ties, but I don’t think tropical kit would have flattered him!

Suez would not have been the first and only port of call and en-route the ship will have docked in other ports and countries.

Sundays may have been the most delineated day of the week when a chaplain took a service on board: whether Dr Motley attended those services I’m unsure but given the precariousness of life at that time if I were to hazard a guess, I’d say yes.

The journey to Suez was via the Cape of Good Hope.

I’ve rationalised this for two reasons - firstly because the Germans and the Italians commanded the Mediterranean and secondly because of the story he told my mother of how he couldn’t go ashore in South Africa for fear of being lynched: for a while I’d slightly doubted the validity of this story but I now believe the opposite and that this would have been the only occasion he was ever in the vicinity and the port of Cape Town.

It also answers two earlier puzzles. When I’d kicked off his story I had wondered whether he had been employed or commissioned as a ship’s doctor and thus in the Royal Navy which of course cast further doubt, but I now realise the occasion of his tale arose from when the troop ship was transporting members of His Majesty’s Services en-route to Suez. Some of the troops of course would have embarked for duty in this part of the continent.

After leaving Cape Town and circling the Cape of Good Hope the ship headed north passing the opening to the Red Sea and then onward to enter the Gulf of Suez.

Thursday 10 November 2022

Wednesday 9 November 2022

Tuesday 8 November 2022

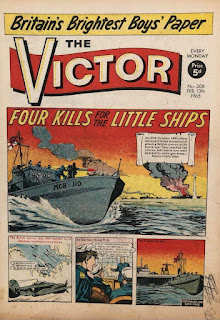

Morgyn the Mighty #1

I’m very rarely on the Oxgangs Blogger (forerunner to the Facebook group) page but I happened to visit it a week or two back. I came across this comment from a Phil Mouldycliff. Similar to Phil this story from early 1965 absolutely fired my 9 year old imagination and remained with me throughout the decades. I’d be up at Ewart’s first thing on Monday morning

hopping about in the shop whilst a bemused patient Ian would find me my copy. 😂

The story is brilliant as is the artwork. It was clearly a life-transforming few

months for Phil. It’s taken a wee while to track down the series in my library.

But now that I’ve done so I aim to post one episode daily over the next 11 days

and for those interested will share the link to the Oxgangs Facebook page. (I’m

assuming I can still remember how to post each blog on Blogger! 🙄)

Hi Peter,

Just belatedly caught sight of your blog relating to the story in the Victor

back in '64 in which Morgyn the Mighty goes to an island full of strongmen

battling to the death. This proved to be the inspiration for me to want to

become a commercial artist and I have always wanted to rekindle my memories of

that particular story. You mention in your blog that you have a complete run of

the adventure. Would it be possible for me to get hold of a copy?

Phil Mouldycliff.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)